Strategic and system-based versus Transactional Approaches in Innovation Based Economic Development

Written By: Karsten Heise, Senior Director of Strategic Programs and Innovation

We are starting off to a new year and this is the time when we are not only reflecting upon the outgoing period but also projecting our wishes, hopes and expectations for the next 12 months. We are contemplating ‘about’ what is likely to happen, including what we wish to happen (even if unlikely) but also bracing ourselves for the unexpected – what may happen that we or others have not thought of – in other words the unlikely event.

In Innovation Based Economic Development (IBED) due to the nature of our business (basically that we are rooted in change),  we probably deal with more of the unexpected than in any other GOED division, although we all encounter our fair share of the unforeseen. Hence, an understanding of uncertainty, its importance for entrepreneurship, and above all an understanding of the environment we are operating in are paramount in order to achieve superior outcomes in innovation based economic development and economic development at large.

we probably deal with more of the unexpected than in any other GOED division, although we all encounter our fair share of the unforeseen. Hence, an understanding of uncertainty, its importance for entrepreneurship, and above all an understanding of the environment we are operating in are paramount in order to achieve superior outcomes in innovation based economic development and economic development at large.

Risk vs. Uncertainty

“Ever since the financial crisis and the pandemic this old economic distinction has witnessed a revival.”

While I first encountered the theoretical concept during my economics degree studies, now more than 30 years ago, those theoretical arguments were essential in understanding the practical workings (and limits) of financial markets during my time on investment banks’ international trading floors dealing with investment management in the second half of the 1990’s and the early 2000’s. These were times of heightened uncertainty with the emerging markets and East Asian financial crisis, the collapse of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) and ultimately the burst of the dot.com bubble (in hindsight all nice trial runs for the great financial crisis some few years later).

The explanations of Risk and Uncertainty also led to and are linked to the far-reaching concept of Complex Systems. Both concepts, understanding uncertainty and the nature of complex systems, enabled a superior approach to investment management such as the development and systematic subsequent application of process, to provide structure and consistency, while taking into account a wide array of views characterized by cognitive diversity and interdisciplinary thinking. Financial markets are subject to uncertainty and are complex systems in nature, thus, lessons do widely apply to the areas of innovation, entrepreneurship and frankly economic development at large.

Both concepts form an essential guide to IBED’s work and are the main drivers why we take a strategic vs. a transactional approach in all projects and initiatives.

Every thorough student of economics will come across the more than a century old distinction between risk and uncertainty going back to economic theorists Frank Knight and John Maynard Keynes. Chicago-based Knight in his 1921 book was focusing on profits. In other words, the reward is how a constantly changing world presents new profitable opportunities for entrepreneurs and businesses, but also an environment characterized by imperfect or no knowledge about future events: entrepreneurial skill (and also luck) navigating environments of uncertainty is driving technological and economic progress.

Cambridge, UK-based Keynes highlighted the formation of long-term expectations, like those that have to be made by entrepreneurs, for actions to be taken in an environment of deep uncertainty in which the future is unknowable and past data offers no guidance while mathematical probability calculations are rendered unusable. Keynes re-expressed Knight’s thinking further and invoked the idea of “animal spirits”, i.e. thought patterns that animate people’s ideas and feelings [1], necessary for entrepreneurial activity to flourish (although Keynes was more concerned with macro-economic factors, the concept is helpful as it stresses the importance of the macro environment some of whose aspects we will invoke below).

What we should take from this is a better appreciation of the importance of uncertainty and that it forms a precondition for the emergence of profitable business opportunities and entrepreneurial activity. Uncertainty gives us options. “Humans thrive in conditions of radical uncertainty when creative individuals can draw on collective intelligence, hone their ideas in communication with others…Uncertainty is to be welcomed rather than feared.” […][2]

Entrepreneurial and Innovation Ecosystems

“Systems’ structures necessitate a Strategic approach and avoiding Transactional Thinking.”

Here at IBED, the notion that conventional economic theory is insufficient to be a guide for delivering superior outcomes enables us to employ approaches, while still solidly grounded in theory, that are more akin to reality.

Here at IBED, the notion that conventional economic theory is insufficient to be a guide for delivering superior outcomes enables us to employ approaches, while still solidly grounded in theory, that are more akin to reality.

The notions of risk and uncertainty are integrally linked to an even more important concept which we diligently follow: the understanding of entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystems as “complex systems” with very specific characteristics that drive our approach, initiatives, and program designs. It also highlights the inadequacy of pure transactional approaches to innovation, entrepreneurship, and economic development.

While the specific workings of a complex system such as entrepreneurial and innovation ecosystems will be the topic of a future blog dedicated specifically to that topic, we are employing a high-level structural analysis here to drive home the argument. The key will be the understanding of how those ecosystems are structured and who the critical members for its efficient operation are.

An innovation ecosystem, much like a natural ecosystem, is comprised of a large diverse number of individuals and institutions who are constantly interacting.

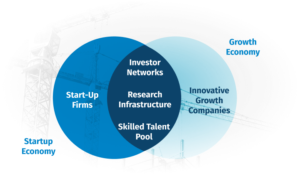

Historically, models like the “Triple Helix” model have been employed to describe such a system. The triple helix model’s components consisted of government and corporations with universities added in the mid-20th century. However, as the IT revolution and the dot.com boom (with subsequent crash) had shown these three actors ceased to have a monopoly on innovation. Enter entrepreneurs and risk capital providers. GOED IBED utilizes a model (depicted above) of an innovation system with two interacting economies consisting of startup firms and established high growth companies respectively. We also adopt the multi-stakeholder model developed by MIT (see graphic).

Historically, models like the “Triple Helix” model have been employed to describe such a system. The triple helix model’s components consisted of government and corporations with universities added in the mid-20th century. However, as the IT revolution and the dot.com boom (with subsequent crash) had shown these three actors ceased to have a monopoly on innovation. Enter entrepreneurs and risk capital providers. GOED IBED utilizes a model (depicted above) of an innovation system with two interacting economies consisting of startup firms and established high growth companies respectively. We also adopt the multi-stakeholder model developed by MIT (see graphic).

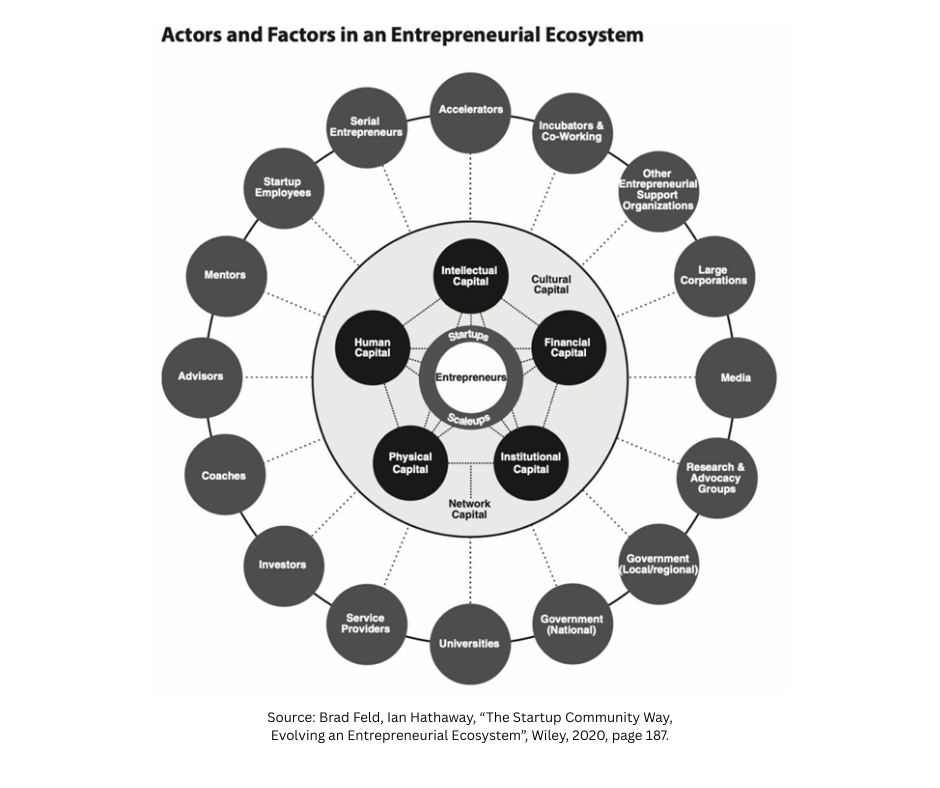

The model represents the minimum viable players [1] required for a well operating innovation system that enables scientific discovery to be translated effectively into applications to societies important challenges and opportunities. Similarly, as far as entrepreneurial ecosystems are concerned, those too consist of multiple and diverse interconnected actors. Here we find Brad Feld’s depiction helpful[2].

Examples of how IBED strengthens Ecosystems

“Programs and initiatives need to strengthen each element within the system.”

We have – at least at a high level – described structures and components of innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystems [5]. Now, how does GOED IBED work in practice to strengthen the effectiveness and impact of those systems?

Our priority lies in devising programs and initiatives that will strengthen each individual component of the system. This is intended to be done in such a way so that each action aims at integrating other elements and creating positive spill-over effects.

Knowledge Fund – Ecosystem: university, entrepreneur, corporate

The Knowledge Fund is a GOED IBED program which advances our state’s innovation-economy by accelerating technology readiness levels, building research capacity, and supporting university startups and deep-tech companies (please see our previous blog for the importance of deep-tech firms).

It is the most critical and only state program to support the translation of research conducted by Nevada’s universities into market applications for economic growth impact. With the Knowledge Fund we are creating new companies that spin out of our research universities; engaging entrepreneurs and company founders as well as establishing connections for high growth firms with university experts who can solve for specific technology problems; providing access to specialized equipment which is often too expensive for startups to acquire; supporting accelerator programs for startups and entrepreneurs through initiatives like the Electrify Nevada Accelerator in partnership with gener8tor or the early stage focused accelerator program with our partner ZeroLabs employing their “innovation launchpad”; demonstrating and validating new water technologies solving for Nevada’s most critical water-challenges, while also attracting water-tech startups via WaterStart; or providing technology test-beds for example for drone innovations through Nevada’s official, FAA-designated Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Test Site Service which is managed through Nevada Autonomous housed under UNR’s Nevada Center for Applied Research (NCAR) itself a Knowledge Fund supported program.

In addition, for deep-tech companies and startups in Nevada, the Knowledge Fund is also sponsoring the Sierra Accelerator for Growth and Entrepreneurship (SAGE), in collaboration with UNR, UNLV, and DRI. SAGE strengthens the technological competitiveness of Nevada small businesses who are seeking funding from the federal Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs also known as America’s Seed Fund.

Battle Born Growth – Ecosystem: risk capital, university, entrepreneur, corporate

The Nevada State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI), Battle Born Growth, overseen by GOED’s IBED, and in particular its state-sponsored venture capital program, is providing much needed risk capital to Nevada’s startups and small businesses. The program does also link to the Knowledge Fund by providing pre-seed stage capital for university spinouts.

This basically means that we are able to support the entire continuum of a company; from its early pre- and formation stage consisting of support at the university level that will enable the inventor and her/ his technology to be paired with an entrepreneur in residence (EIR) or an externally identified CEO. This is accomplished in order for a business to be created and to be spun out of the research institution. This is then followed by potential support for continuing to validate the technology through testing at the university lab, and ultimately after the company’s spin-out from the university, providing pre-seed risk capital through our state-sponsored venture capital program.

Office of Entrepreneurship – Ecosystem: entrepreneur, risk capital, university

Supporting entrepreneurs and founders broadly is a priority for IBED. Our Office of Entrepreneurship. Its mission is to ensure that every entrepreneur, regardless of their path, has access to the resources, technical support, and funding they need to succeed. The Office serves both Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as well as Innovation Driven Enterprises (IDEs) as described above. Importantly, services provided are tailored to the specific type of business as SMEs and IDEs due to their distinct nature require different types of support. For example, improving access to capital for these enterprises would mean microloan or financing or providing collateral support in the case of SMEs, while IDEs seek specialized venture/ risk capital.

These examples illustrate how IBED program support and work with all the other four stakeholders in the ecosystem (entrepreneurs, risk capital, university, and corporate) and how individual programs and initiatives interact.

Transactional approaches are still prevalent but need to be replaced by a systems-approach

“Transactional thinking still dominates because it appeals to human nature.”

While the term “ecosystem” has entered the general vocabulary, its deeper meaning is less well understood and its use far too casual. Decision makers within a system speak of “ecosystems” but often still behave purely transactional. For example, in higher education grant opportunities are often pursued in isolation, that is while other stakeholders of a system are frequently being involved in the application and execution process for the duration of the grant, the grant itself is often not strategically embedded within a system including not being sufficiently connected to other initiatives and prior grants to ensure a long-term holistic strategy. As a result, the ‘grant consortium’ often breaks up after the completion of the grant and new opportunities are being pursued with duplication over time being not an infrequent phenomenon.

Similarly, in government when GOED makes the case for funding for our key IBED programs [6] legislative review regards those program funding decisions as a pure ‘budgetary transactional decision’. Those decisions are based, apart from the general fund’s fiscal situation, on “individual success stories” viewed in isolation whereas support should be evaluated on how the program addresses and supports as many key actors within the system, direct and indirectly and as effectively as possible.

The net result of that approach has been that the Knowledge Fund, to name one program as an example, has received far less allocations, most certainly when compared to other states[7], than required to effectively strengthen innovation and entrepreneurial systems.

In other words, we are only able to produce “proof of concepts” on a continuous basis but are unable to enter required scale-up phases for broad economic impact.

As the functioning ability of those systems lies at the core of how innovation based economic development works. Innovation being the main guarantor for economic growth in the first place, and the under-allocation of resources in this instance reduces Nevada’s economic growth both from a potential- as well as real growth perspective.

These two examples of a transactional based approach mirror human nature. “Humans are predisposed to reduce problems into discrete situations that can be solved analytically one at a time” […][8]. Holistic thinking is not often applied and we favor viewing the world through our personal experience lens, and solution selection is often influenced by our own familiarities. We avoid embracing realities, such as in innovation and entrepreneurship, through a systems approach because of a desire to avoid uncertainty and seeking to be in control [9].

At GOED IBED we recognize that Nevada’s innovation systems (and entrepreneurial ecosystems as sub-systems) are complex (adaptive) systems in their composition of actors and in how those systems behave. That it is they are made up of large networks of components or stakeholders with no central control and are governed by simple rules of operation that give rise to collective, self-organizing behavior. Thoughtfully managing complexity requires a suitable theoretical framework to guide which inputs and levers to adjust to stimulate the types of self-organizing behavior that lead to economic growth and prosperity. One framework is the abovementioned MIT stakeholder framework.

The overarching message is that for innovation based economic development to be successful that is to achieve superior economic growth and produce high-paying employment opportunities, a transactional approach is inherently insufficient and detrimental.

[1] G.A. Akerlof and R.J. Shiller, “Animal Spirits Among Us”, https://reflections.yale.edu/article/money-and-morals-after-crash/animal-spirits-among-us

[2] J. Kay and M. King, “Radical Uncertainty, Decision-Making Beyond the Numbers”, Norton, 2020.

[3] Phil Budden, Dame Fiona Murray, “Accelerating Innovation, Competitive Advantage Through Ecosystem Engagement”, MIT Press, 2025.

[4] Brad Feld, Ian Hathaway, “The Startup Community Way, Evolving an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem”, Wiley, 2020, page 187.

[5] We will address the working and characteristics of such systems in a later blog.

[6] The Knowledge Fund is a good example here.

[7] In the run-up to the 2025 Nevada Legislative Session, we conducted a comparative analysis of a selected number of states that have been investing strategically in innovation and found that using 2022 US Census Annual Survey data that the percentage of state-tax-revenue spent on innovation initiatives by those states ranged from 0.16% to 1.3% of state tax revenue. This is compared with Nevada’s average annual investment in the Knowledge Fund which represents a mere 0.03% of state-tax-revenue!

[8] Brad Feld, Ian Hathaway, “The Startup Community Way, Evolving an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem”, Wiley, 2020

[9] ibid